As a result of taking the course "Indigenous Research Ethics" at the University of Arizona with Dr. Stephanie Carroll, the Data Sciences Academy team felt the need to create a virtual space for us to grow a community of Indigenous and Indigenous serving educators interested in Indigenous Data Sovereignty for our K-14 students. This work stemmed from our work in Natives Who Code, serving tribal communities through computer science education.

We give our gratitude to the authors that are featured on this page and to Dr. Stephanie Carroll for the opportunity to engage in discussion around these topics presented. Lastly, we would like to invite our colleagues in Indigenous Education, globally, to join us in our learning and resource building for today's native youth to learn of the growing Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance movement. Say hello with this form!

Ahéhee', Thank you,

The Data Sciences Academy team

Background Artist Credit: John Pepion | Urban Indian Health Institute

So, you're here. You're curious. You're an advocate for Indigenous Data Sovereignty and want to do your part as a K-14 educator. Where do you start? We start by educating ourselves on the current landscape. We then move to community building and networking with like minded individuals. This is the step the DSA team is at and we are intentionally entering into Relational Accountability with the tribal communities we serve across the state of Arizona.

From Dr. Carroll et al.'s paper "Indigenous Data Governance: Strategies from United States Native Nations" from the section "Recommendations to Strengthen Indigenous Data Governance", we see the mention of "data warriors".

Tribal Rightsholders

- Develop tribe-specific data governance principles

- Develop tribe-specific data governance policies and procedures

- Generate resources for Indigenous data governance by tribes

Stakeholders

- Acknowledge Indigenous data sovereignty as a global objective

- Build an Indigenous data sovereignty framework that specifies the relationships among data processes such as collection, storage, and analysis.

- Create intertribal institutions dedicated to data leadership and building data infrastructure and support for tribes

- Develop mechanisms to facilitate effective Indigenous data governance

- Establish data governance mechanisms that non-tribal governments, organizations, corporations, and researchers can use to support Indigenous data sovereignty

- Explore the complexities of individual and collective rights in relation to Indigenous data sovereignty

- Explore the relationships among ethics, law, data governance in relation to Indigenous data sovereignty

- Grow financial investment in Indigenous data infrastructure and capability

- Identify common principles of Indigenous data governance

- Incorporate Indigenous data sovereignty rights into all rightsholders’ and stakeholders’ data policies

- Promote adoption and implementation of common principles of Indigenous data governance by tribes, governments, organizations, corporations, and researchers within the United States

- Recruit and Invest in data warriors (Indigenous professionals and community members who are skilled at creating, collecting, and managing data)

- Share strategies, resources, and best practices

- Strengthen domestic and international Indigenous data sovereignty and Indigenous data governance connections among Native nations and Indigenous peoples3

We believe today's K-14 Indigenous student population have rights to learn of the IDSov/IDGov movement and need direct support and investment to become tomorrow's Data Warriors.

Below are the recommended first steps in educating you and your community in the Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance Movement

In our community dialogue, in a learning setting, let's discuss our initial ideas.

First, from the National Academy of Medicine, The Culture of Health Program, we given the following,

Principles for Community Conversations

Respect and honor all voices, embracing diversity and all worldviews.

Listen without interruption and participate actively.

If you're someone who tends to speak a lot, consider leaning back. If you're someone who tends to be quiet, consider leaning forward.

Be open to hearing about perspectives and experiences that differ from your own or that challenge you.

Entering the community valuing unknowing and with the recognition that we are all here to learn and grow.

Acknowledge when a comment is difficult to share and take the risk.

Give space for thought.

Speak from your own perspective instead of speaking for others. You are an expert of your own lived experiences. Office advice only when it is welcome or asked for.

Assume best intent, but own your impact.

As a community that is learning, let's consider the following discussion questions.

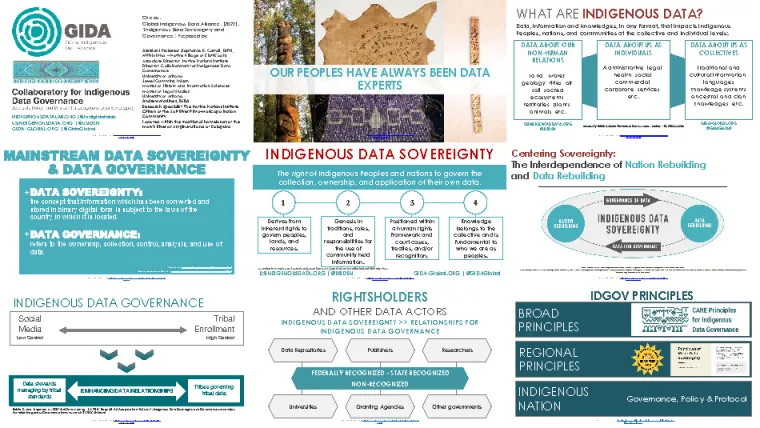

- What is data?

- What is Indigenous Data?

- What is Indigenous Data Sovereignty?

How does this concept impact you and your community and work?

In all of our learning, we are humbled and immensely grateful for those Indigenous global leaders in this movement. Let's further explore the resources that follow. These resources are crafted with you, our Indigenous relatives in mind.

Link to Recorded Science Seminar: Implementing the CARE Principles in Open Data Repositories

Prepared by:

Assistant Professor Stephanie R. Carroll, DrPH, MPH(Ahtna – Native Village of Kluti-Kaah) Associate Director, Native Nations Institute Director, Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance University of Arizona

Jewel Cummins, Intern

Master of Library and Information Sciences

Master of Legal Studies

University of Arizona

Andrew Martinez, BSBA

Research Specialist, The Native Nations Institute

Citizen of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community Located within the traditional homelands of the Mary's River or Ampinefu Band of Kalapuya

Indigenous data sovereignty reinforces the rights to engage in decision-making in accordance with Indigenous values and collective interests.

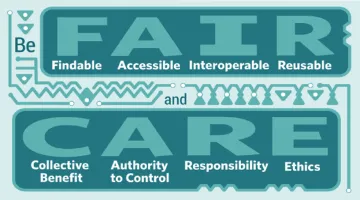

"The current movement toward open data and open science does not fully engage with Indigenous Peoples’ rights and interests. Existing principles within the open data movement (e.g. FAIR: findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable) primarily focus on characteristics of data that will facilitate increased data sharing among entities while ignoring power differentials and historical contexts. The emphasis on greater data sharing alone creates a tension for Indigenous Peoples who are also asserting greater control over the application and use of Indigenous data and Indigenous Knowledge for collective benefit. This includes the right to create value from Indigenous data in ways that are grounded in Indigenous worldviews and realise opportunities within the knowledge economy. The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance are people and purpose-oriented, reflecting the crucial role of data in advancing Indigenous innovation and self-determination. These principles complement the existing FAIR principles (www.go-fair.org) encouraging open and other data movements to consider both people and purpose in their advocacy and pursuits."

The existence of massive data, its extensive reuse, the increasing ability to mine data and to use artificial intelligence to learn from data calls for the need to have a formal framework that articulates the approaches necessary for the use of data that is consistent with cultural and collective rights of Indigenous Peoples.

As our students become more and more acutely aware of their role as data scientists in a world filled with the impact of artificial intelligence, instruction in computing from the earliest stages should be grounded in the FAIR and CARE Principles.

“As one of the core course requirements of the First Nations graduate education degree, students were expected to learn about current educational issues as they were expressed in several First Nations communities. To gather this information, each researcher was expected to live in an unfamiliar community: to become immersed in the life of the community; to interview, observe, and learn from the people there.” (Wilson-Wilson, pg.155)

Your positionality statement is an intentionally crafted statement that briefly explains your background and the priorities of your work. From the authors, Curran and Randall,

- How the identities of the authors relate to the research topic and to the identities of the

participants and how these identities are represented in the scientific record / journals

(Roberts et al., 2020, page 11). - Short video description: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GpcIVzGYhVs

Although definitions may vary, it is widely agreed that there are nine principles involved in operationalizing of CBPR:

- Recognize the community as a unit of identity.

- Build on the strengths and resources within the community.

- Facilitate a collaborative, equitable partnership in all research phases through an empowering and power sharing process that attends to social inequalities.

- Foster co-learning and capacity building among all partners.

- Integrate and achieve a balance between data generation and intervention for the mutual benefit of all partners.

- Focus on the local relevance of public health problems and on ecological perspectives that attend to multiple determinants of health.

- Involve systems development in a cyclical and iterative process.

- Disseminate results to all partners and involve them in the wider dissemination of results.

- Involve a long-term process and commitment to sustainability.

(Hébert et al., pg.43)

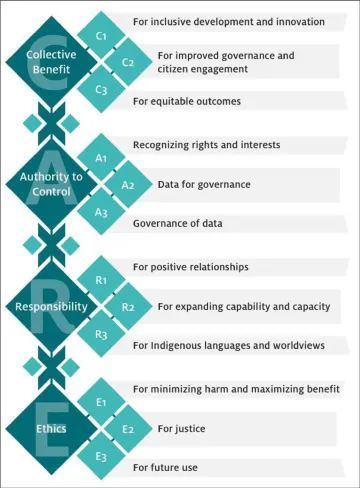

The CARE Principles and Their Supporting Concepts

"Indigenous data must facilitate collective benefit for Indigenous Peoples to achieve inclusive development and innovation, improve governance and citizen engagement, and realize equitable outcomes. Benefits accrue when data ecosystems are designed and function to support Indigenous nation and community use and reuse of data; use of data for policy decisions and evaluation of services; and creation and use of data that reflect community values.

UNDRIP affirms Indigenous Peoples’ rights and interests in their data. Recognition of these rights bolsters Indigenous Peoples’ authority to control and govern such data, further affirming the need for ‘data for governance.’ Indigenous Peoples must have access to data that support Indigenous governance and self-determination. Indigenous nations and communities must be the ones to determine data governance protocols, while being actively involved in stewardship decisions for Indigenous data that are held by other entities.

When working with Indigenous data, there is a responsibility to nurture respectful relationships with Indigenous Peoples from whom the data originate. Aspects of the relationship include investing in capacity development, increasing community data capabilities, and embedding data within Indigenous languages and cultures. Pursuing these goals fulfills the ultimate responsibility of supporting Indigenous data that advances Indigenous Peoples’ self-determination and collective benefit.

Indigenous Peoples’ rights and wellbeing should be the focus across data ecosystems and throughout data lifecycles in order to minimize harm, maximize benefits, promote justice, and allow for future use. Paramount to ethics in data practices is representation and participation of Indigenous Peoples, who must be the ones to assess benefits, harms, and potential future uses based on community values and ethics." (Carroll et al., The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance)

Examples of Indigenous Jurisdiction

TribalCrit

"This is central to the particularity of the space and place American Indians inhabit, both physically and intellectually, as well as to the unique, sovereign relationship between American Indians and the federal government. My hope is that TribalCrit can be used to address the range and variation of experiences of individuals who are American Indian." (Brayboy, 430)

TribalCrit on Power

"Power through an Indigenous lens is an expression of sovereignty—define as self-determination, self-government, self-identification, and self-education. In this way, sovereignty is community based. By this I mean that the ideas of self- determination, -government, -identification, and -education are rooted in a community’s conceptions of its needs and past, present, and future. Deloria (1970) extends and crystallizes this point when he writes, ‘‘Since power cannot be given and accepted...The responsibility which sovereignty creates is oriented primarily toward the existence and continuance of the group’’ (p. 123). Power, as I define it, is the ability to survive rooted in the capacity to adapt and adjust to changing landscapes, times, ideas, circumstances, and situations." (Brayboy, 435)

Continue your learning journey in IDSov and IDGov through these established organizations working collectively for the rights of Indigenous peoples and their data.

Recommended Reading

Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Towards an Agenda

Open source book: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1q1crgf

Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Policy

Open Source Book: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/oa-edit/10.4324/9780429273957/indig….

Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous data futures

Open Source Article: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-021-00892-0

Indigenous Data Governance: Strategies from United States Native Nations

Open Source Article: https://datascience.codata.org/articles/10.5334/dsj-2019-031

QR Code to share this website!